After December 2019, when the first case of the novel 2019 coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) was identified, the associated illness (COVID-19) became a significant international health concern. Declared a global pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020) on 11 March 2020, COVID-19 remains one of the most catastrophic and unprecedented public health crises in decades. It resulted in over 534 million reported cases worldwide and 6.3 million deaths as of 16 June 2022 (WHO, 2022), with numbers continuing to rise as new strains with potentially more harmful effects are identified.

The impact of COVID-19 on pregnant women has been the cause of much controversy. The focus of current literature regarding this cohort of the population has been two-fold. Studies have either concentrated on the infection's effects on mother, baby and the pregnancy or evaluated the possibility of vertical transmission from a pregnant mother to her fetus in utero, during delivery or in the postpartum period. With regards to the former, several studies have highlighted that coronavirus infections lead to more severe complications and negative outcomes in pregnancy, including renal failure, disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, preterm deliveries, fetal growth restriction, a greater chance of intensive care admission, intubation and mechanical ventilation and spontaneous miscarriages, stillbirths or perinatal deaths (Schwartz and Graham, 2020). Normal physiological changes occurring during pregnancy are thought to underpin the rationale for pregnant women being more susceptible to developing these negative outcomes (Kourtis et al, 2014). Cardiopulmonary adaptations as a result of the gravid uterus predispose to hypoxaemia, while variations in sex hormone levels and their interaction with the immune system hinder pathogen elimination and exacerbate infection severity (Kourtis et al, 2014).

Regarding the possibility of vertical viral transmission, there has been no definitive confirmation of intrauterine transmission of any coronavirus species to date (Diriba et al, 2020; Schwartz and Graham, 2020). However, several published case reports make this a controversial subject for COVID-19. One study identified a positive neonatal pharyngeal swab 3 days after an emergency caesarean section, although placental and cord blood samples tested negative (Wang et al, 2020). Furthermore, in a review of 128 newborns, five tested positive for COVID-19 viral genetic material while six others tested negative but had elevated antibodies against the virus instead. However, alternative samples including vaginal secretions, breast milk, amniotic fluid, cord blood and placental tissues were all negative, refuting the possibility of vertical viral transmission (Chi et al, 2021).

Following the introduction of universal COVID-19 screening for all inpatients at the North West Anglia NHS Foundation Trust to identify asymptomatic positive patients and reduce the spread of COVID-19, newborn babies were also included. Between 28 April and 21 May 2020, 410 babies born at two maternity units within the trust were screened using nasopharyngeal swabs and reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Nine newborns tested positive within 24 hours of delivery while eight of their mothers tested negative (McDevitt et al, 2020).

In the unprecedented time of a global pandemic, several screening and diagnostic tests were initially used in an attempt to identify infected individuals and control the spread of COVID-19. From the authors' personal experiences, initial opinions regarding the accuracy and reliability of these COVID-19 tests were extremely varied, with many unclear as to the best option to use when testing patients in healthcare settings. Furthermore, the effects of COVID-19 on pregnancy, mothers and newborn babies are still under investigation. More research is needed to enable definitive conclusions to be drawn and fundamentally, more mothers need to opt to participate in this research. To facilitate this and influence future clinical practice, mothers' opinions regarding neonatal and maternal testing for COVID-19 were considered in this study and the consenting process for these investigations was reviewed.

Methods

This service evaluation aimed to assess the existing service provided to women for neonatal and maternal COVID-19 testing.

The inclusion criteria included pregnant women who had been admitted to the trust and screened for COVID-19 by trained midwives using nasopharyngeal swabs and the SARS-CoV-2 RT-PCR test between 28 April 2020 and 21 May 2020. All neonates born within the trust whose mother consented to them being screened for COVID-19 in the same way were also included. The exclusion criteria were women who had suffered miscarriages, stillbirths or terminations of pregnancy during the time frame. Altogether, 494 mothers and 410 babies were included and 13 were excluded.

All 494 women were initially sent an invitation to participate in the service evaluation. This provided details regarding the rationale for the project, an explanation of how it would be conducted, clarification that participation was voluntary, not compulsory and confirmation that all information gathered would be anonymised and kept confidential. It also highlighted the possibility of the findings being published in order to increase the number of women consenting to participate in research relating to COVID-19 and influence future clinical practice while advancing global knowledge of the impact of COVID-19 testing on patient experience. The invitation also provided information on who to contact if they declined to participate. The women were then given 4 weeks to make a decision before being telephoned. Details of the initial invitation were reiterated and any questions the women had were answered before they were asked to verbally consent to participating.

A questionnaire with mostly closed questions and pre-determined answers (yes, no, unsure, cannot remember, vaguely, undecided or N/A) was designed to assess whether mothers (and their newborn babies):

- Were offered a nasopharyngeal COVID-19 test

- Felt this was optional or compulsory

- Worried about the results while waiting for the outcome

- Felt sufficiently informed about the risks and benefits of being tested

- Understood the implications of a positive result

- Would consent to testing in future pregnancies.

The questionnaire also included optional, supplementary, free-text questions to enable women to explain their responses. These included reasons why they did or did not worry about the results of their swab, did or did not understand the implications of a positive test and would or would not endorse testing in future pregnancies. When reviewing the answers to these questions, it was clear that the same set of responses were repeated, which allowed them to be grouped for ease of interpretation.

Ethical considerations

Prior to the start of this study, advice was sought from the trust's Research and Development Department and Information Governance Department on ethical approval. By evaluating opinions regarding neonatal and maternal COVID-19 testing and the current consenting process for these investigations, future clinical practice within the maternity and neonatal services at the trust could be reviewed and beneficial changes made. It was therefore confirmed that the project did not require any formal ethical approval and should be completed as a service evaluation.

Results

Analysis for maternal swabs

Of the 494 women, 292 (59.1%) consented to participate. Of these, 289 (99.0%) confirmed they were offered a nasopharyngeal swab while three (1.0%) reported they were not. A total of 285 (98.6%) consented to having the COVID-19 swab while four (1.4%) declined.

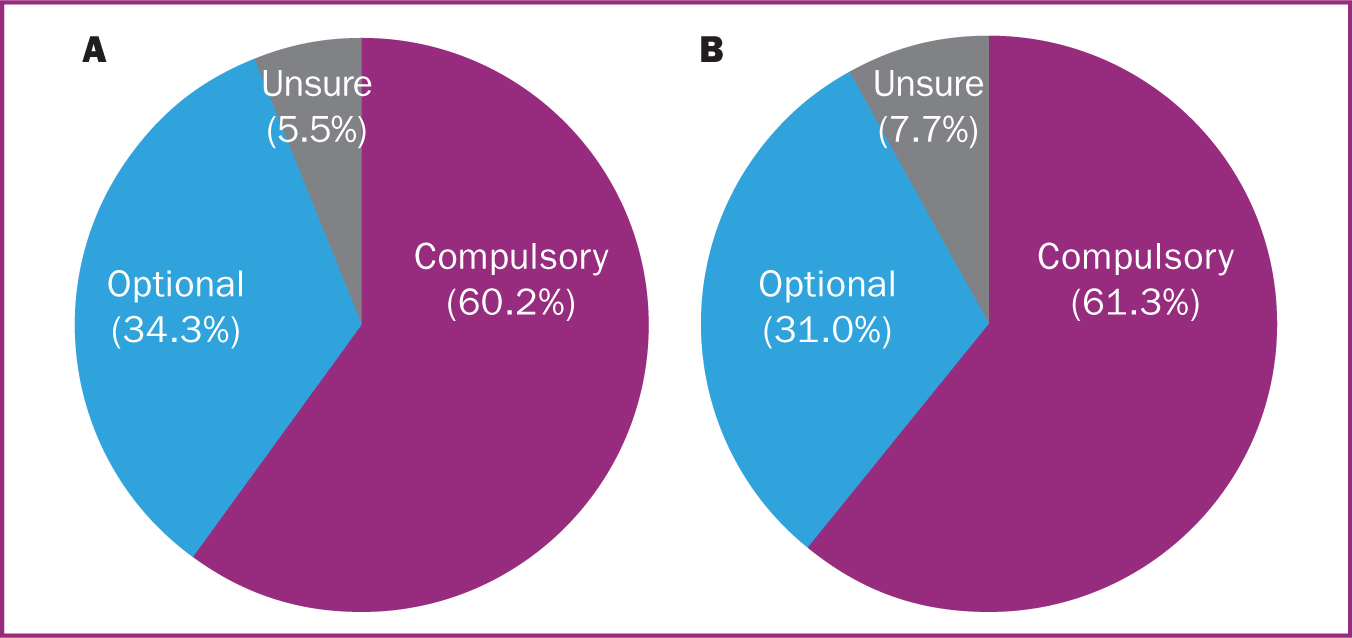

Figure 1a shows maternal opinion as to whether the women who were offered a swab felt it was optional or compulsory. Most (60.2%) reported they felt the swab was compulsory.

While waiting for the swab results, 78.5% reported that they did not worry about their result because they assumed it would be negative after isolating for the duration of their pregnancy. Another 20.4% did worry, mainly because of increasing reports of asymptomatic carriers and the possibility of contracting COVID-19 despite strictly adhering to government guidelines. Only three participants (1.1%) could not remember whether they were worried at the time or not.

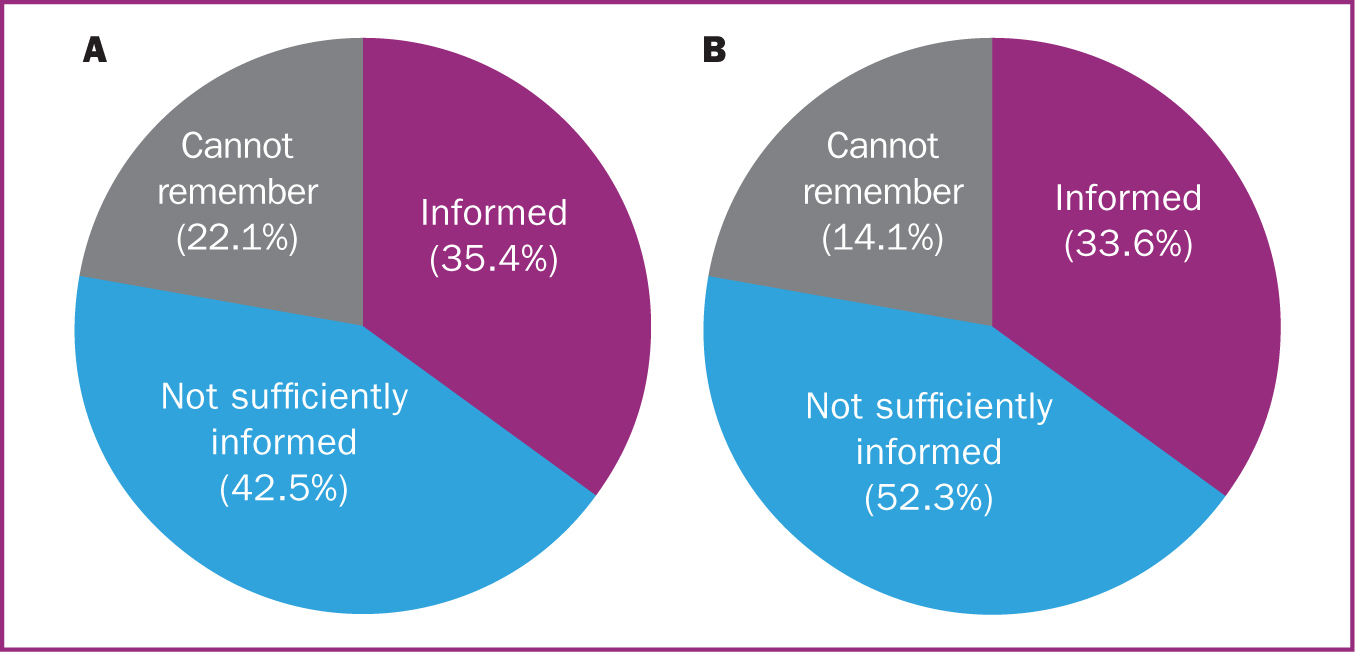

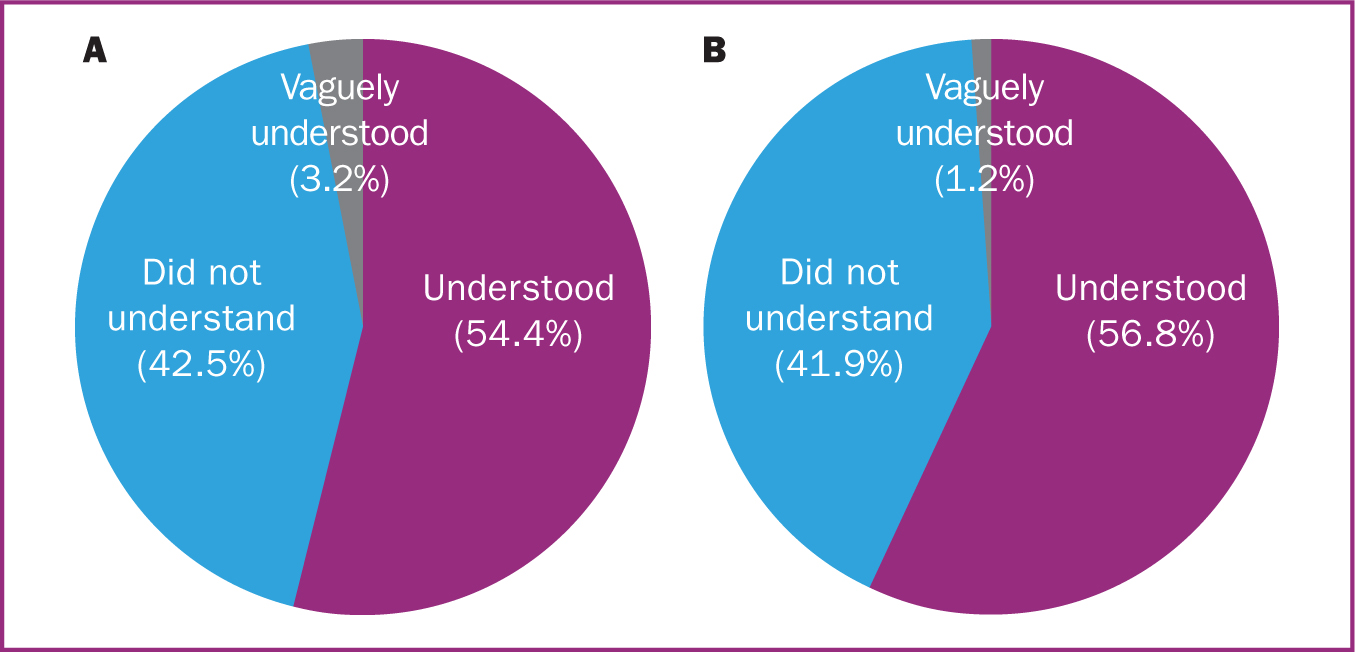

Of the 285 women who were swabbed, 35.4% felt they were sufficiently informed about the risks and benefits of being tested, 42.5% did not and 22.1% could not remember (Figure 2a). When asked whether they understood the implications of a positive test result for themselves, their new baby and the rest of their family 54.4% felt they understood, 42.5% did not and 3.2% felt they only vaguely understood the implications (Figure 3a). Those who reported they vaguely understood felt that they knew what was expected with regards to isolating but wanted more clarification on specifics such as whether they would still be able to breastfeed or not. Five participants (1.8%) tested positive for COVID-19 and of these, four felt satisfied that they were informed about how to manage this, although one did not.

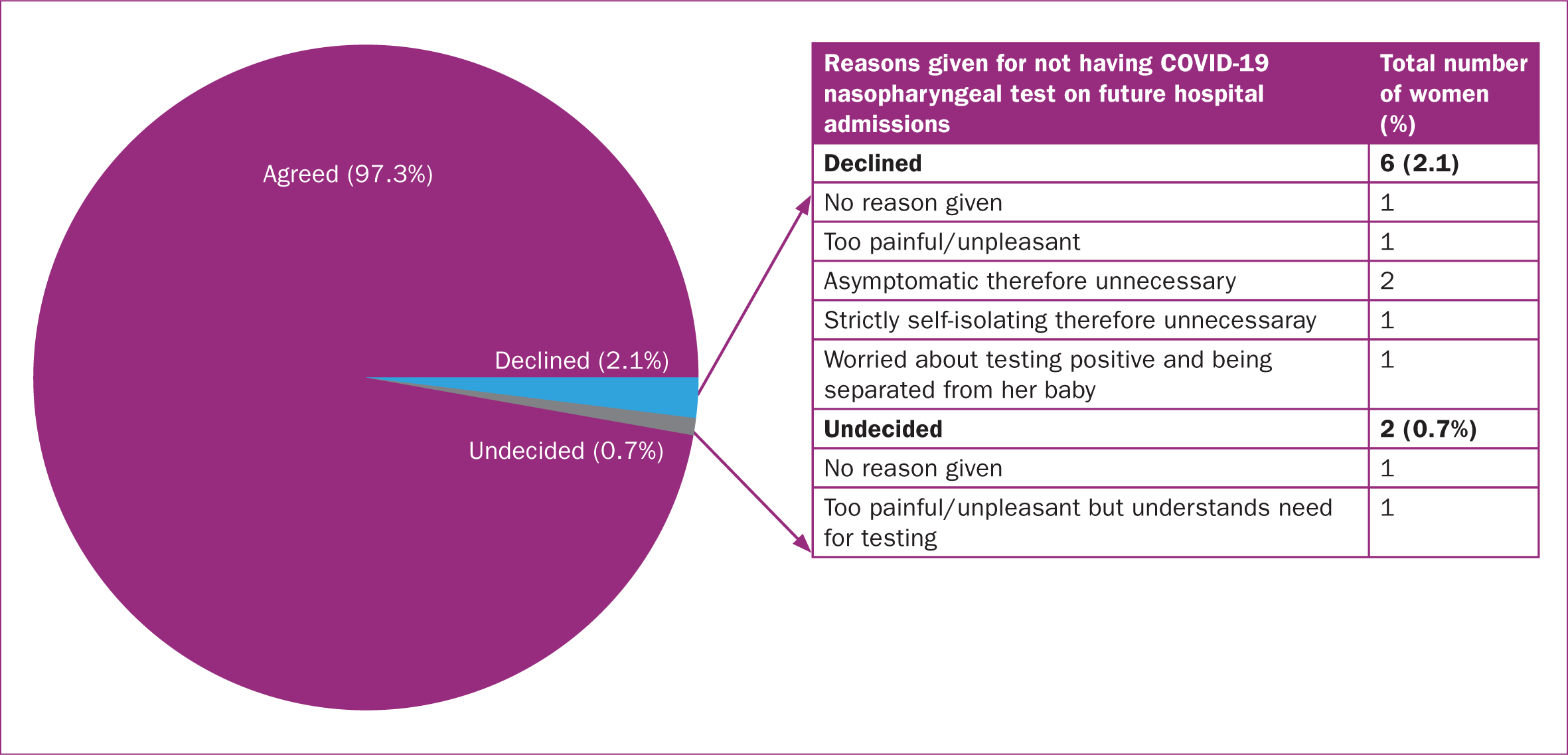

When asked whether they would consent to testing in future pregnancies, 97.3% of participants agreed. Interestingly, this included the four who declined the swab on this admission. However, six (2.1%) others declined while two (0.7%) were undecided, the reasons for which have been illustrated in Figure 4.

Analysis for neonatal swabs

Of the 292 mothers, 84.9% confirmed that their newborn baby was offered a COVID-19 swab and of these, 97.2% went on to have one taken while seven (2.8%) declined. Of all 292 women, 14.7% denied or could not recollect being offered a test for their baby. While 12 (27.9%) of these 43 women were admitted during the dates included within the study (28 April 2020 and 21 May 2020) and were tested for COVID-19 themselves, they delivered after 22 May when newborn testing had been discontinued as per revised local trust policy.

Maternal opinion regarding whether their baby's swab was optional or compulsory is shown in Figure 1b, with very similar percentages to those in Figure 1a.

While awaiting the swab outcome, 72.1% of participants reported that they did not worry about their baby's result. Reasons given included the fact that they themselves were asymptomatic, their own swab had been negative, they had strictly isolated during the pregnancy, their baby was tested within a few hours of birth and all staff in contact with their baby were wearing appropriate personal protective equipment. For some women, they simply stated they had other things on their mind having just given birth.

The remaining women reported that they did worry about their baby's result. Several who gave birth at the start of the pandemic recounted how the doubt and ambiguity of the impact of COVID-19 on pregnant women and the potential for vertical transmission caused a great deal of anxiety. Many women reported uncertainty regarding the implications to their baby's care if they were found to be positive, particularly relating to the possibility of being separated while in hospital. Others reported concerns about increasing evidence of asymptomatic carriers of the virus.

Of the 241 mothers whose babies were swabbed, 33.6% felt they were sufficiently informed about the risks and benefits of being tested, 52.3% did not and 14.1% could not remember (Figure 2b). Regarding whether they understood the implications of their baby testing positive, 56.8% felt they did, 41.9% did not and three (1.2%) only vaguely understood (Figure 3b). Of the 241 newborn babies who were swabbed, six (2.5%) tested positive for COVID-19 and of these, three (50.0%) mothers felt satisfied that they were informed about how to manage this and look after their baby safely while the other three did not.

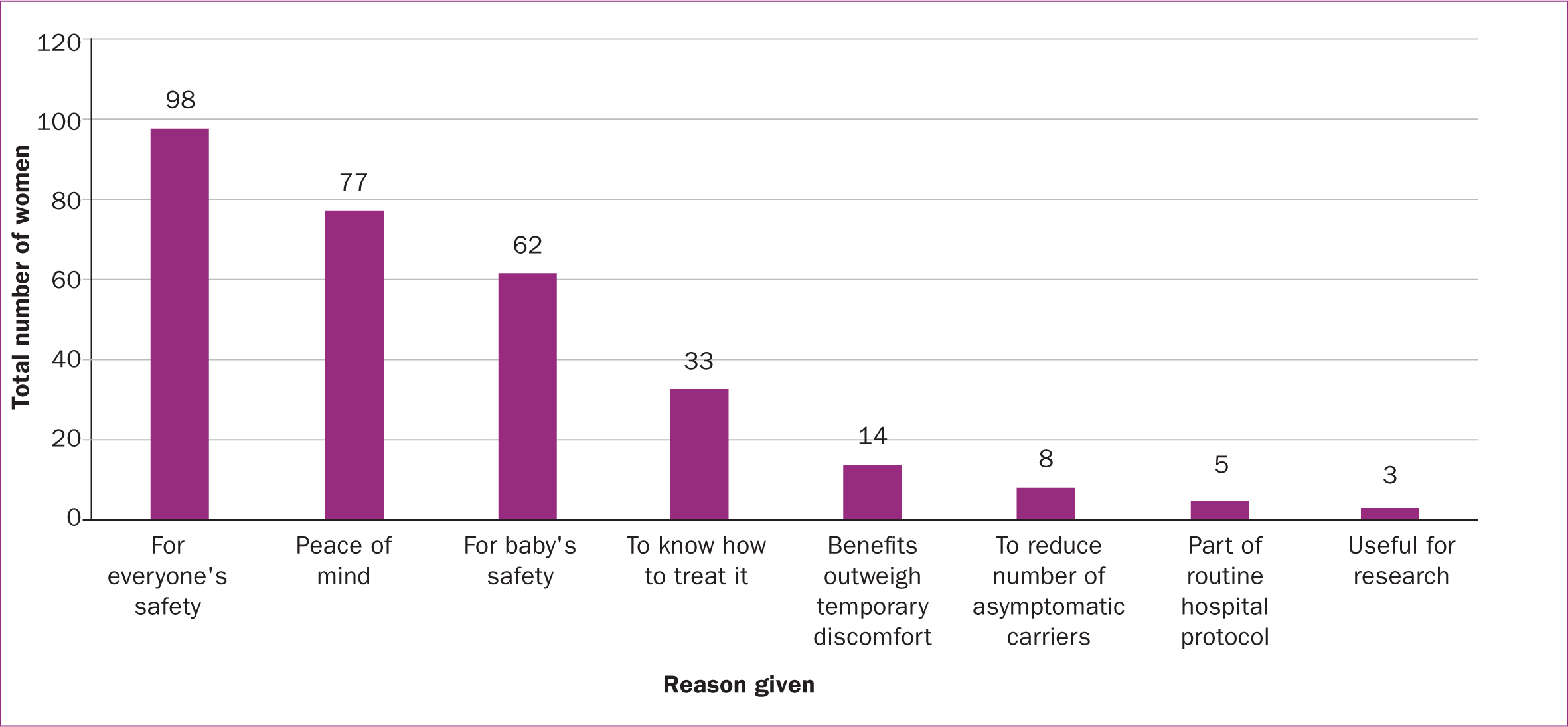

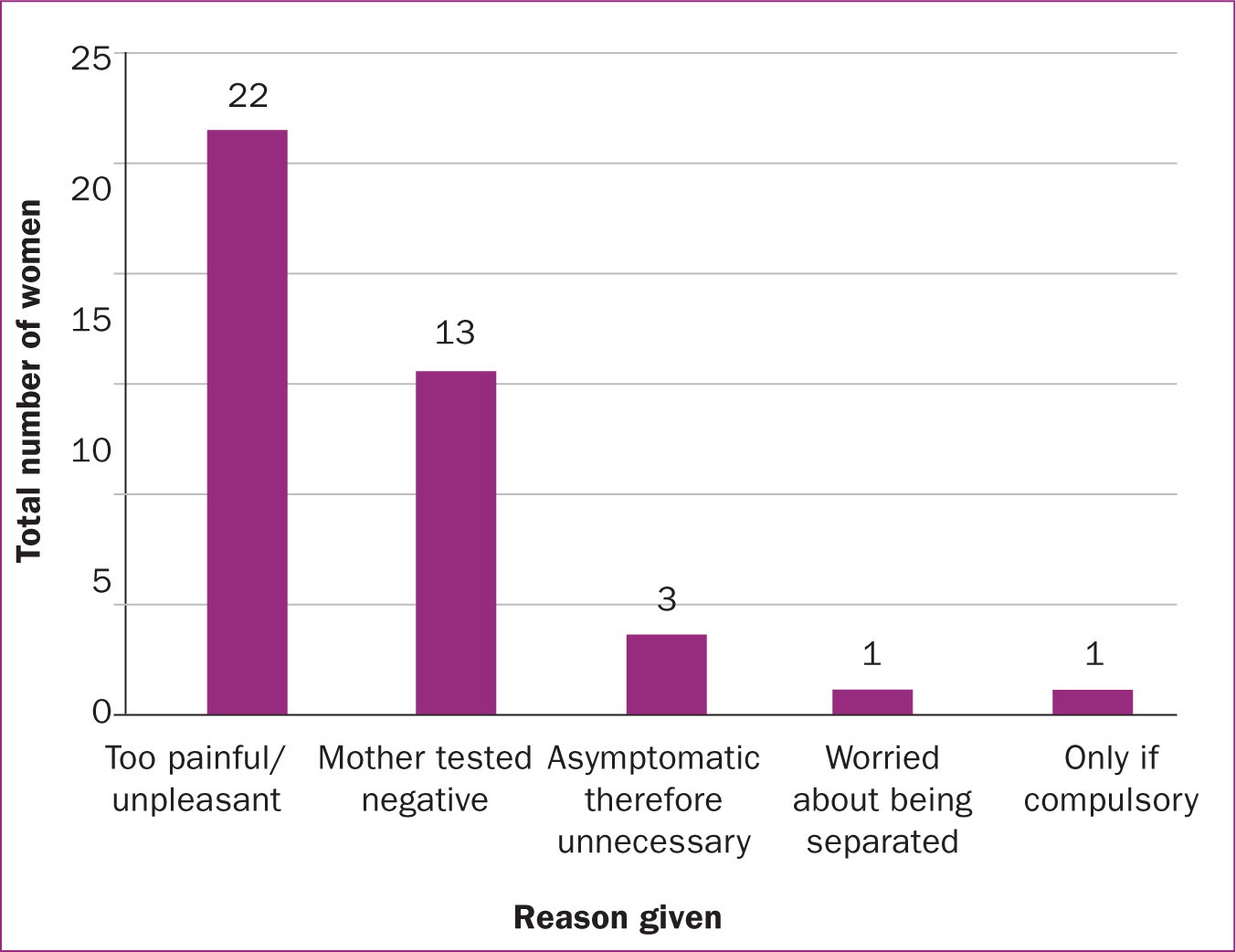

Of the 292 women, 85.6% agreed to neonatal testing in future pregnancies while 7.2% declined and 7.2% were undecided. Figure 5 shows the reasons given by those who agreed (the most common of which was ‘for everyone's safety) while Figure 6 shows the reasons given by those who declined (the most common of which was ‘too painful/unpleasant’). In both groups, many women provided more than one reason.

Discussion

The principal finding of this service evaluation was that communication to women and the information provided regarding maternal and neonatal nasopharyngeal COVID-19 testing (the swabbing process, risks and benefits of being tested and the implications of a positive result) was critical to obtaining valid, informed consent and required improvement. This was emphasised by the fact that the majority of women felt their own and their baby's COVID-19 swab was compulsory rather than optional (when it was in fact optional), while many did not feel sufficiently informed about the risks and benefits for themselves or their baby being tested. Furthermore, just under half of the participating women did not feel they understood the implications of a positive test result on the rest of their family and only half of those whose baby tested positive felt satisfied with the information provided regarding how to manage this.

From the results of this study, it is clear where women felt under-informed and required further clarification. This information can be conveyed to healthcare professionals taking swabs so that these aspects are emphasised and covered in more detail. If this is addressed, this should lead to an increase in the number of women giving valid, informed consent for testing in the future.

However, while it is important to acknowledge and act on these findings to increase the number of women who consent to themselves and their baby being tested, it is also important to contextualise these results. At the time of testing, the pandemic was still a novel concept and, as such, the uncertainty and lack of information for both healthcare professionals and patients alike regarding the COVID-19 swabbing process at this early stage of the outbreak was understandable. Now that there is more information available about COVID-19, and patients and healthcare professionals are more accustomed to the protocols in place if they or a close contact test positive, it should be easier to ensure informed consent is attained appropriately, although this remains to be seen for certain.

Another important finding of this service evaluation was the identification of two fundamental reasons why women declined testing (for themselves or their newborn baby) during this admission and would continue to do so in future pregnancies. The first reason was the anticipated physical pain caused by the swab itself combined with the emotional trauma to a mother who saw her baby was distressed after the test. The latter appeared to have a greater influence on women's decision to decline testing, as 22 of 40 responses (55.0%) gave this reason to justify why their babies would not be tested in future pregnancies, while only two of eight responses (25.0%) provided this reason for why the women themselves would decline future testing. It is possible these findings are the result of the fact that women have been found to be more anxious about the pain induced by nasopharyngeal probing and experience slightly more discomfort compared to men (Marra et al, 2021; Moisset et al, 2021).

The second reason why women declined testing was because of ongoing uncertainties over the necessity of the test when appropriate precautions were taken during pregnancy. This was supported by the observation that the majority of women did not worry about their own or their baby's result when awaiting the outcome. Given the retrospective nature of this service evaluation, it is likely that these reasons preceded the now more acknowledged contributory role of asymptomatic carriage in COVID-19 transmission. Asymptomatic carriage and transmission of COVID-19 has become increasingly publicised since the outbreak of the pandemic (Lee et al, 2020) with some studies calculating that over half of all transmissions occur before an infected individual develops symptoms (Johansson et al, 2021). In a study of over 1000 healthcare workers, 3% tested positive despite being asymptomatic for COVID-19 (Rivett et al, 2020). It is evident that the detection of asymptomatic carriers was fundamental to controlling the spread of the disease (Johansson et al, 2021) and this should encourage more women to have themselves and their baby tested in the future.

The final key finding identified by this service evaluation was that the majority of women would consent to themselves (97%) and their newborn baby (86%) being tested for COVID-19 in future pregnancies. The primary reason for doing so was to ensure the wellbeing and safety of everyone, including the women themselves and their newborn baby, the hospital staff, other patients, family and friends. The second main reason for opting in was for peace of mind and the reassurance of knowing that their baby is safe (if the swab is negative) or how to treat and manage it (if the swab is positive).

Strengths and limitations

This is the first service evaluation to explore maternal opinions regarding information giving and consent for maternal and neonatal nasopharyngeal COVID-19 testing within the literature to date. A large proportion of women (nearly 300 mothers) responded and opted to participate, a significant number that adds strength to the findings. However, given that only service users from a single trust were included, the results cannot be generalised to the entire population. Future research should aim to include larger populations to enable more definitive conclusions to be obtained.

One limitation of the service evaluation was that it was undertaken in the format of a questionnaire. This may not have been the most reliable form of data collection, as women may have felt pressured to answer a certain way. This could have been because they knew that they were speaking to healthcare professionals from their local hospital, even though it was reiterated that the information they provided would be kept anonymous and confidential. Additionally, the project was performed retrospectively, with the swabs collected between April and May 2020 and the women contacted to participate a few months later. Between these two time periods, significant advances in COVID-19 research were made and extensively publicised and, as such, maternal opinions may have changed since the time when the swabs were taken in the early stages of the pandemic.

Conclusions

In meeting the initial aims established for this service evaluation, maternal opinions regarding nasopharyngeal COVID-19 swab testing for pregnant women and their newborn babies were explored and a detailed account provided for the first time within the current literature to date. Important and novel information was identified and overall, the majority of women favoured continuing with testing. However, it is evident that information given to women to obtain informed consent requires improvement and needs to include the swabbing process, the risks and benefits of being tested or not and the implications of a positive test result. This should increase the number of women who give informed consent for themselves and their baby to be tested in future and subsequently contribute to ongoing research related to COVID-19. As COVID-19 continues to evolve, it is important that additional service evaluations are undertaken to provide further insight into opinions regarding maternal and neonatal testing regimes to facilitate future research related to this cohort of the population and influence future clinical practice.

Key points

- While coronavirus infections cause severe pregnancy complications, no definitive confirmation or mechanism of vertical transmission of COVID-19 has been identified and further research is required.

- Newborns have been found to test positive for COVID-19 within the first 24 hours of life despite eight of their mothers testing negative.

- Individual views regarding available screening tests for COVID-19 are varied and maternal opinions regarding testing are yet to be elucidated.

- To increase participation in research, communication to pregnant women regarding all stages of the COVID-19 swabbing process is critical and requires improvement.

- This study highlighted areas where women felt under-informed, which can be conveyed to healthcare professionals to be covered in future.

- Promisingly, the majority of women reported they would ultimately agree to testing for themselves and their baby in future pregnancies.

CPD reflective questions

- Do healthcare professionals truly obtain consent in an informed way?

- Do midwives obtain consent from women appropriately and provide information on what is known as well as what is not?

- How can consent for neonatal swabs be improved? Would patient information leaflets be useful?

- How are women informed and advised if their newborn baby tests positive for COVID-19?